We knew it would happen and it has. The first mega, unspinnable example of the shambles permeating the Trump shit show in his hastily assembled cabinet of hams. And it couldn’t have happened to a journalist they hate more – not a Fox talking head who could be bullied into silence but the reputable editor of The Atlantic Jeff Goldberg who handled his mistaken inclusion in a classified group chat of a live debate between 18 top officials – including J.D. Vance and Pete Hegseth discussing air strikes against the Houthi terrorist group in Yemen with a measured outrage that made them look even more ridiculous. I happened to watch an interview with the volume off of Defense Secretary Hegseth’s attempt to explain during a layover en route to Asia. The Pentagon chief, chosen for his matinee-idol looks and strong jaw, suddenly looked like a mean, exploding insect as he tried without success to trash Goldberg as a lying leftie, a “so-called journalist who's made a profession of peddling hoaxes” and flailed that “Nobody was texting war plans.” Goldberg, backed up by screen shots of the explosive thread, calmly responded to CNN’s Kaitlan Collins, “That’s a lie.”

Houthigate may just be the first debacle that penetrates the somnolent public’s psyche about the Trump administration’s incompetence. For a scandal to land with a bang, it has to be simple to explain. All the Democrats attempts to put Trump behind bars or impeach him were riddled with layers of snoozy legal nuance that bored the public or simply passed them by and the Trump sex scandals were just baked into his brand. In our rushed digital age, there is no one alive whose heart hasn’t dropped with the realization that an individual insult has been sent as Reply All, or the subject of mockery copied into a thread. An incident such as this, one of rampant sloppiness on a matter of maximum national security, stands in for all the rest of the mayhem now taking place at multiple government agencies where DOGE and Trump are ensuring years of professional expertise are going out the window. I wish I could pretend to be more woeful about an outrage so endangering to America, but, long term, it’s a horror show that is oddly heartwarming. It could be just the necessary pivot point that starts to generate Trumper unease.

Worms Unite

Cowardice is contagious. Once upon a time, we could feel superior to the shameful moral turpitude of Congress, but then big media owners caved, Silicon Valley founders groveled, and now the once respected white-shoe law firm Paul,Weiss, former home of such legal legends as Ted Sorensen, Adlai Stevenson, and Arthur Goldberg, has folded like a deck chair. (Not a peep of protest, by the way, from Paul, Weiss partner and Obama’s former Homeland Security director, the sainted Jeh Johnson.) So much for Watergate hero John Dean’s assertion in Vanity Fair last year that he never met anyone who wasn't proud to have been on Nixon’s enemies list.

In his latest blizzard of malice, Trump banned Paul, Weiss attorneys and staff from working for the government or having security clearances — mostly, it seems, as revenge for Paul, Weiss veterans Mark Pomerantz going after Trump for falsifying business records in the Stormy Daniels case, and Robert Mueller for filing a suit against January 6ers. Paul, Weiss chairman Brad Karp, who, as head of a private firm, has no shareholders to answer to, whimpered about the potential hit to the firm’s business as his rationale for agreeing to follow the new White House laws dismantling DEI, take on $40 million in Trump-blessed pro bono work, and “engage experts…to conduct a comprehensive audit of all of its employment practices.” According to The American Lawyer, other unnamed law firm chairs see this last capitulation as the most threatening, resembling “a monitorship, similar to how the Communist Party needs to have a representative in every law firm in China." Next stop, the selective piercing of the veil of attorney-client privilege? We should all root for another Trump target: Perkins Coie, the Seattle-based law firm that repped Hillary in 2016 and is brandishing its cojones in court.

In her new book of essays Notorious, Maureen Dowd quotes Barry Diller in March 2018 waving off the Trump phenomenon. “I want this to be a moment in time where you go in and pick out this period with pincers and go on with life as we knew it before,” he told her. Seven years later, it’s clear that the Trump event is not an aberration. It’s an era. When he and his MAGA movement have finally gone, it will take more than pincers to root out the corruption and mend the broken talent torn down by the 47th president and toy-smashing toddler Elon Musk in their frenzy of disruption. As has just been proved by Hegseth and Co’s security fiasco, it takes layers of deep mastery, moral texture, and precedent to run a functioning democracy. It's often said these days that Trump thinks he's a king. In fact, he operates as a crime boss, shaking down his adversaries, demanding—insisting on—obeisance, and twisting his knife into the soft flesh of sycophants as the cameras roll.

Jeff Goldberg’s scoop was all the more cheering because it restored a rightful fear of watchdog media, an antidote to the dispiriting trend noted in Oliver Darcy’s trenchant newsletter Status. He highlighted a small but telling clue as to how fast great media companies have crumbled, just in the language they chose to report the returning space shuttle’s splashdown on Friday. “A review of transcripts, courtesy of SnapStream, revealed an alarming reality,” he writes. “Not one of the outlets could muster up the courage to simply refer to it as the Gulf of Mexico, the water feature’s name since the 16th century.” He continues:

“On ABC News, "World News Tonight" anchor David Muir referred to "spectacular images from off the coast of Florida." On the "NBC Nightly news," anchor Lester Holt spoke about the astronauts "splashing down off the Florida Gulf coast." On the "CBS Evening News," it was referred to simply as "the Gulf." And on CNN, anchor Jake Tapper tried to seemingly have it both ways, noting the U.S. government refers to it as the "Gulf of America," but the rest of the world calls it the Gulf of Mexico.

In fact, I could only find one instance on a television newscast where a journalist referred to the body of water as the Gulf of Mexico. During an appearance on MSNBC, NBC News correspondent Tom Costello used the term, but then quickly corrected himself, almost as if he had realized he was forbidden from doing so. “Six hours from right now, there will be a splashdown in the Gulf of Mexico,” he said, before backtracking. “Sorry, however you want to call the Gulf. It will be splashing down in the Gulf.

Suffice to say, none of this was an accident. Television news organizations have standards departments that think hard about these sorts of issues and issue guidance about the network's positioning on them. In other words, each of the outlets made a willful decision to forgo referring to the Gulf of Mexico as the Gulf of Mexico. While it may have been performed in a subtle manner, make no mistake: It was still an act of submission.”

Democracy dies by Sharpie

One Thousand and One Nights in a Dinner Jacket

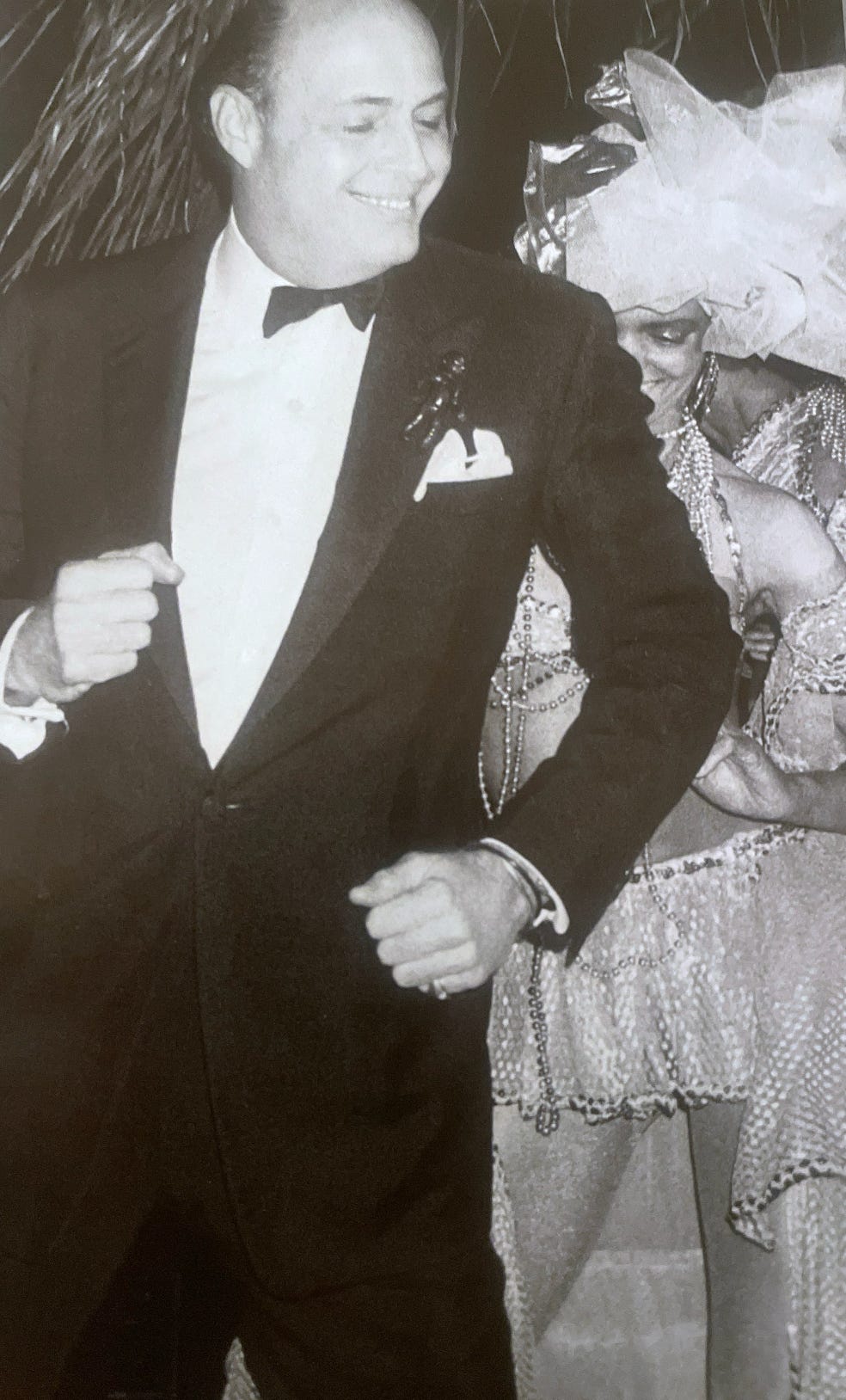

I was crushed to read on my vacation last week of the death of the Venezuelan-born social arbiter and best-dressed boulevardier Reinaldo Herrera at the age of 91. Most knew Reinaldo as the eternally suave Manhattan-based husband of the fashion designer Carolina, but, in many masthead-invisible ways, he played a critical role in the success of my editorship of Vanity Fair in the 80s and early 90s.

I first caught sight of him on the island of Mustique in 1980, slicked-back hair shining with pomade, in a conga line of aristos with Carolina at a party for Princess Margaret. Nothing about his impeccable tailoring or casual hauteur betrayed the inner Reinaldo I came to love. In 1984, six months into my editorship, VF writer Bob Colacello brought Reinaldo into the office and he was so entertaining I hired him immediately as a contributing editor. The son of the 4th Marquis of Torre Casa, Reinaldo had once worked as a journalist on a morning TV show in Caracas and he never lost his instinctive news flair. He always called me Fearless Leader, or Fearless for short.

Every place I have worked as an editor, I have tried to deploy certain contributors whom most of the other employees considered bafflingly superfluous. This is because most journalists are too high-minded to value social energy, or to understand what Jane Austen knew so well, that everything happens at parties. Reinaldo was invaluable because he was out every night of the week at the top social events in Manhattan and, like a golden retriever in a dinner jacket, he always brought in stories the next morning. “My dear, it’s all over with Gloria Vanderbilt. I saw her carried out last night from Mortimer’s absolutely blotto.” “Fearless, I heard from Sirio (the legendary maitre d’ at Le Cirque) that Richard Nixon is coming in to lunch tomorrow with, of all people, Lynn Wyatt!” (He immediately booked me the table next to them for lunch.)

Reinaldo was especially good at wrangling the wives of despots for Vanity Fair profiles. Had you tried traditional channels to finagle access to such notorious personages, it would have been futile. But because Reinaldo socialized with the high and was always courteous to the low, he was usually my first call. “Imelda Marcos?” (The infamous first lady of the Philippines who salted away billions of pesos from the Filipino people and is most remembered for possessing more than 1,000 pairs of shoes and a peerless collection of purloined canary diamonds.) “Charming woman! Her dinners at the Malacañang Palace were always so perfectly seated! I am sure she would be delighted to meet with Dominick Dunne!” (She was less delighted with Dunne’s riveting VF piece in 1986, which asserted that the drab villa where Imelda then lived in ignominious exile in Hawaii had a "there goes the neighborhood" feel about the place.) In 1989, reporters at multiple news outlets were baffled as to how VF’s foreign correspondent T.D. Allman got to fly on Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat's private jet for forty hours, through four countries, with an open notebook. Allman wrote, “He sat twenty inches away, his knees touching mine, in the seat facing mine…. The plane was too tiny to carry a stewardess, so the chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization took over: ‘Tea or coffee?’" The reason T.D. was experiencing the twinkly side of a man the U.S. government considered an “accessory” to terrorism was because Reinaldo improbably knew Arafat’s barber. “I shall call him tomorrow, Fearless, and find out when we can get to him.”

Given how rarely the pieces that Reinaldo had brokered turned out as the subjects expected, one might expect him to have occasionally taken umbrage. But his natural buoyancy and passionate loyalty to Vanity Fair allowed him to somehow sail past any brief social embarrassment that ensued. Every so often, he tried to exact payback by asking me to include some boring Park Avenue friend's Italian villa in a design feature. Usually he accepted my brusque rejection of such ideas with good grace, but he had clearly overshot his skis on the Italian villa assignment and had promised it without asking. After ten minutes of listening to his baritone grumbling, I told him we had plenty of fancy real estate in our pages, such as the German princess Gloria von Thurn und Taxis’s turreted palace in Bavaria. “Fearless, there are people you and I know who would simply get up and leave the room if the Thurn und Taxises walked into it,” he said sorrowfully. I gave him the Italian villa spread in recognition of his multiple other successes.

Over the years, I came to see Reinaldo’s impeccable comportment as a moral quality. He felt it was on him to elevate the room and leave people feeling better about themselves. Perhaps that is the definition of the outdated concept of manners. Why was it once considered de rigueur when seated between two people at a dinner party to spend the first course talking to the one on your right and the second to the one on your left? So that neither of them felt left out. Why was it once considered beyond the pale to drop out of an event with an hour’s notice, or to show up without the expected plus one? Because it insulted the host’s careful planning. The same is true of being late. My time is of more value than yours. When less refined people chose the wrong fork at a dinner hosted by the Queen Mother, I am told she also chose the wrong fork to avoid any risk of her guests’ embarrassment.

Reinaldo was a prized member of the small, traveling social army I always brought to events that publicized Vanity Fair. He understood a magazine is a team effort and was always willing to romance an advertiser or rescue a shy guest. It was rare that his social self-confidence was misplaced. At a VF Hollywood charity benefit for the drug rehab center Phoenix House, I discovered in a panic that, thanks to party designer Robert Isabell's last-minute decision to bring in a “lighting genius” to dip the candelabra light bulbs into tubs of magenta dye, we’d gone $15K over budget, a bad look for a charity gala aiming to hit a million-dollar fundraising target. Of course I turned to Reinaldo. “Don’t worry, Fearless,” he replied equably. “I will call my friend Al Taubman” (the stonking rich owner of Sotheby’s at the time). Clearly he didn’t remember that Taubman had recently hit the roof when the British writer James Fox, in a profile of the French purveyor of call girls Madame Claude, had fallaciously hinted that Taubman’s wife Judy, a former Miss Israel, was one of them. Reinaldo waived away that caveat. “Alfred is a friend,” he said. “I will simply call him and say, ‘Hallo Alfred, this is Reinaldo. I’m in a bit of a bind. I’ve asked 500 people for dinner on Thursday and find I have no lighting. Can you give me $15,000 for the cause?’ ” As I sat imagining how the volatile cheapskate Taubman would react to such a request, Reinaldo returned very quickly, murmuring that perhaps he had called his friend at an inconvenient time. (We eventually got the money from the gangster Sam Giancana’s former mistress in Las Vegas, who fortuitously had very much liked Dominick Dunne’s profile in another issue. Those were the days.)

After I moved from Vanity Fair to The New Yorker, I saw less of Reinaldo. He continued to thrive in the Graydon Carter regime, resolving to help him with the same gusto that he had helped me make his beloved Vanity Fair the talk of the town. I last saw him a year ago when I was thinking of writing a book about the Niarchos dynasty, three generations of whom he knew. He was happy to see me, but I noticed that he occasionally gazed off into the distance and forgot names. “The fish is very good here,” he said. “Let me order for you.” And then, perhaps suddenly aware that this was something he could no longer do, he put his hand over mine and said, “No, Fearless, why don’t you order for me?”

As courtesy, kindness, and consideration seep away in public life, how I shall miss you dear Reinaldo.

Two very different examples of humanity brought alive by Tina’s writing genius.

"EVERYTHING HAPPENS AT PARTIES."