Happy 100th anniversary, The New Yorker, still my favorite brain food in print and online! My six and a half years as its editor were some of the most exhilarating of my life.

It was a warm June day in 1992 when Condé Nast’s diminutive and mercurial chairman S.I. Newhouse Jr., “Si” to all who worked for him, summoned me to his 14th floor office strewn with R. Crumb comics. It would be the second time he’d ask me to edit the crown jewel of his publishing empire, a magazine that had only three (male) editors in its 67-year history. Si had offered me the job a year earlier, but I had dithered. With an increasingly geriatric readership and advertising in a nosedive, its prospects were shaky. And with two children under the age of five, the idea of facing weekly deadlines (instead of my monthly rhythm as editor of Vanity Fair) had been too daunting, a problem solved when my parents agreed to move from the UK and live in an apartment across the hall. Plus, I felt that the magazine’s DNA didn’t fully resonate with me as Vanity Fair's did. There was a stuffy, windowless quality to its book-length articles on deliberately arcane topics. What was the point of coming out weekly if you were running a piece on beekeeping the week that General Noriega was stealing the Panamanian election? I tended to agree with Tom Wolfe -- that The New Yorker had become “easier to praise than to read.”

Si, however, grew up worshiping The New Yorker, which he bought in 1985 for $168 million in cash. He revered its equally diminutive and reclusive editor of 35 years, William Shawn, at least until he realized how much money he was losing. In February 1987, he fired Shawn and installed another of his heroes, Knopf’s editor-in-chief Robert Gottlieb, one of the world’s greatest book editors. Gottlieb’s drawback was that he admired the magazine so much, it made him a hostage to its problems. On the June day that Si urged me again to make the move, he was at his desk doodling in the yellow pad on which he liked to list the advertising pages missing from all the magazines he owned.

My dithering stopped after a deep dive into the musty, bound copies of the magazine’s first quarter century (1925-1951), under the editorship of Harold Ross, its eccentric and profane co-founder with his wife Jane Grant, often written out of the story. I felt that destiny, or destiny’s assistant, had just called. This was a magazine with many windows! It exuded an urbane adrenaline and visual flair, with full-page drawings by Peter Arno and Charles Addams, not squinty little cartoons dropped in as punctuation. Its “Talk of the Town” section featured pungent squibs of reporting instead of ambling mini-essays, and the magazine had a permeating irreverence that had latterly been suffocated. Yet, as I kept going, I saw the influence of Shawn, working under Ross in the 1940s, introducing thrilling, innovative reporting like John Hersey’s “Hiroshima,” which took up the entire issue, and Rachel Carson’s environmental bombshell “Silent Spring.” This earlier incarnation of The New Yorker was a magazine I could relate to and even, with luck, recreate. The prospect of restocking the talent cupboard with all the dazzling writers there had been no room to include in Vanity Fair quickened my heart. The mission was nothing short of saving America's bastion of beautiful sentences and intellectual rigor. I was intoxicated by its high standards and shall always be grateful to Si who believed that I could rise to the challenge.

Fading Fedoras

My first meeting with the New Yorker senior editors took place in a boardroom at a table lined with middle-aged white men in coke-bottle glasses. A Frank Zappa look-alike, who turned out to be the cartoonist Bob Mankoff, stood glowering at the back. He was convinced I was going to kill the cartoons and replace them with photos of celebrities. (In fact, I promoted him to cartoon editor, created a Holiday Cartoon issue, and urged Si to buy Bob’s side venture, the Cartoon Bank, a commercial enterprise that sold the cartoons we didn't buy.)

The staff of The New Yorker (and pretty much everyone in the world of print media) saw my appointment as sacrilege. I was, after all, the lady editor who, eleven months before, had put the naked and very pregnant Demi Moore on the cover of Vanity Fair. Where was the gravitas? The veteran New Yorker writer George W. S. Trow called me “the girl in the wrong dress.” Garrison Keillor, the hayseed humorist from “Lake Wobegon,” quit. Jamaica Kincaid called me “Stalin in high heels.” (There’s some truth to that one.)

The other day, I stumbled upon a file of letters Si Newhouse wrote to one of the many New Yorker readers who canceled their subscriptions when they learned of my appointment. “Dear Mr. Hickman,” reads one Si missive from September 3, 1992. “Let me try to resolve your dilemma about resubscribing to this magazine... I believe that doctrinal rigidity would lead to timid publishing, an unacceptable position for The New Yorker…. I can assure you that high ambition, a sense of quality and a respect for the English language will define Ms. Brown’s editing philosophy as they have her predecessors…. However you may eventually judge her New Yorker, I can assure you you won’t be bored.” It’s unthinkable that any media owner of his stature would take the time to write such a letter today.

My mandate from Si was to clean house and blood-change the reader demographic. The magazine, it turned out, was an editorial Augean stables, with all kinds of strange contractual arrangements. The office was overflowing with writers who never had time to actually write, such as Joseph Mitchell, who was the stuff of literary legend, but whose byline hadn’t appeared in the magazine since 1964. He still haunted the corridors in a brown fedora. Behind another closed door resided Ved Mehta, the blind Indian essayist, at work on another installment of his thousand-part autobiography. My inbox was stalked by the feted highbrow fiction writer Harold Brodkey, with his papyrus-toned bald head and faint Hannibal Lecter sneer, who would send me seven-page faxes at midnight demanding to know why he was being overlooked (though not why he was being overpaid).

Then there were the other “old guard” writers whom I treasured. Far from disapproving of our changes, this group loved the new energy from the youth infusion. They included Roger Angell, the sublimely vivid baseball writer and fiction editor, John Updike, Lillian Ross, Brendan Gill, and Philip Hamburger, whom I discovered had written the magazine’s eyewitness account of Mussolini’s corpse being strung up with that of his mistress in the Piazzale Loreto in Milan. I adored these wonderful old literary pros with their can-do typewriters and dauntless approach to a deadline. In the blizzard of 1998, they were the only ones to come to work in their galoshes. I often went to lunch with the tiny, devious octogenarian Lillian Ross, whose profile of Ernest Hemingway remains a startling joy to read, and who had been William Shawn's mistress for decades. Even after his death, she was still locked in a psychic duel with his even tinier wife Cecille.

Over the course of three years, I let go of 71 staff writers and hired 50, most of whom are still there: from London, the 30-year-old film critic Anthony Lane, whose brilliant prose walks a tightrope between Waugh and Wodehouse; from the Washington Post, the creative brainiac Malcolm Gladwell (one of whose first contributions was a column titled “The Tipping Point”); from the Wall Street Journal, the dogged investigative sleuth Jane Mayer; and from Harvard’s African American Studies department, Henry Louis Gates Jr., who I converted from an academic to one the magazine’s most original profilists of the likes of James Baldwin, Colin Powell, and Harry Belafonte, collected in his anthology Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Man. Skip, as he is always known, lobbied me to bring on as an editor an omniscient 20-something Renaissance man, Henry Finder, still in position today in the august role of editorial director. I wrangled out of Texas Monthly the compelling storyteller Lawrence Wright and, casting around for a reporter on legal issues, alighted on a high-energy assistant U.S. attorney named Jeffrey Toobin, whose first two pieces were so clunky that I killed them. As a last resort, I suggested he go to LA and follow the breaking case of a murder investigation involving O.J. Simpson. Toobin shed the legalese, located his narrative flair, and owned every plot twist of the story.

A most consequential day was spent reading the unpublished manuscript of a book about post-Yeltsin Russia titled Lenin’s Tomb, written by the Washington Post’s young Moscow correspondent David Remnick. I invited him to lunch at The Four Seasons with a view to hiring him. Sometimes people ask me what I first saw in Remnick, to which the answer is everything. It soon became clear that he not only wrote like an angel (with a speed and productivity that made envious colleagues weep), but also possessed a rare moral maturity, unfailing collegiality, and a commitment to The New Yorker’s standards that applied not just to his own contributions but to those of everyone else.

My secret weapon in coming to grips with all of this was my former Vanity Fair managing editor Pamela McCarthy, who, with a deftness unknown to Elon Musk, attacked the tottering infrastructure and modernized the machine. My judgment consigliere was Hendrik Hertzberg, who’d grown up at The New Yorker and who knew which writers were there because they were good, as opposed to those who thought they were good because they were there. Hertzberg never wrote a bad sentence, often demonstrating his wit and style under other people’s bylines. When I tossed him an unpublishable fashion report by the former Interview editor Ingrid Sischy, it come back as de Tocqueville. I thought one of the magazine’s precocious treasures, the art critic Adam Gopnik, needed a new gig and sent him off to become the Paris correspondent, resulting in his best-selling essay collection Paris to the Moon. I arm-twisted British literary dazzler Simon Schama, Cambridge historian and author of Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution, to transmogrify into one of The New Yorker’s culture connoisseurs.

It was full on, all the time. Working through the nights while our children slept, Pamela and I rewired the New Yorker management as a matriarchy with editors like Susan Morrison (currently enjoying great success with her biography of Lorne Michaels), executive editor Dorothy Wickenden, who could reshape and salvage the most recalcitrant gibberish by press time, and in Washington, Susan Mercandetti, a former ABC producer who came up with the news scoops. They all had children themselves. We colluded like a secret society about how to meet the deadlines and still get to Field Day. I still remember their nannies’ names.

Cover Stories

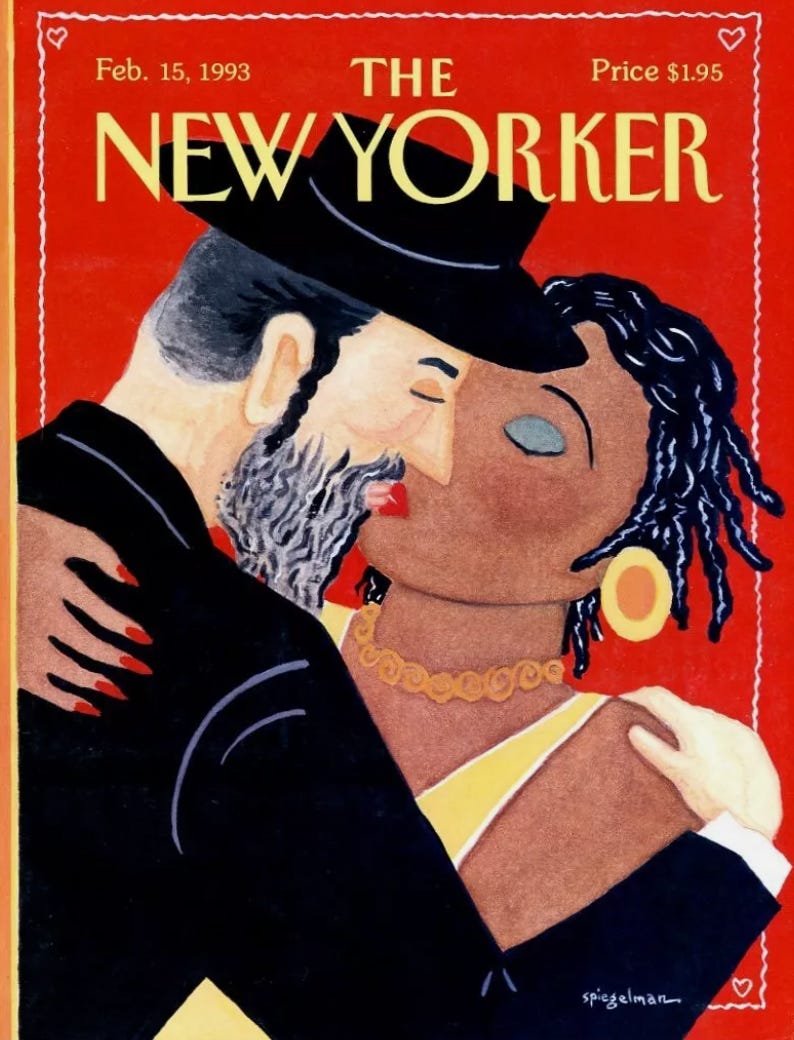

And then there was the joy of the visuals. My debut cover in October 1992 by Edward Sorel was a sly reference to my subversive reputation, showing a leather-clad punk lolling in the back of a horse-drawn carriage in Central Park with a shocked top-hatted driver holding the reins. It was our way to announce that the age of droopy visual politeness was over. I brought in Art Spiegelman, the Pulitzer Prize-winning creator of Maus, to make the right kind of trouble with such now iconic images as a Hasid kissing a black woman, in the wake of the Crown Heights race riots.

It was a point of honor to me to never back down from one of Art’s controversies, but I admit I felt trepidation when, at the start of Holy Week, I published his cover of an Easter bunny crucified on an IRS tax form. It drowned me in a tsunami of fury from the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights and the Jewish Anti-Defamation League. An anxious Remnick looked out his office window to see thousands of people, led by a man with a crucifix, coming down Broadway on a Good Friday march and panicked, thinking they were coming for us. Spiegelman introduced me to his art director wife, the brilliant Françoise Mouly, who had glamorous, exploding dark hair and an impeccable eye for talent. I fell in love with Françoise on the spot and put her in charge of the covers thereafter. At The New Yorker cover art show this past January at L’Alliance Française, I was in awe at the iconic cadre of artists she has recruited in the last 32 years to reinvent the dying art of magazine illustration.

I could see the pages coming alive, but I still missed something the magazine never had: full-page photography. I knew it had to be sparing. It had to be black and white, and have the purity of Rea Irvin’s signature Caslon typeface. In short,it had to be Richard Avedon, who became The New Yorker’s first and only staff photographer, a position his ego relished, and whose concept of expenses became clear when he handed a pile of bills to Pamela McCarthy in a Tiffany box tied up with a ribbon. With design director Caroline Mailhot, we redesigned the magazine back to front. There were charges of blasphemy when we introduced such vulgar additions as bylines, or a Table of Contents page so you actually knew what was ahead. The Caslon typeface wasn’t touched; its distinctive elegance was like a truth serum that exposed bad writing. The back page was reinvented with an old New Yorker title “Shouts and Murmurs” and became a recurring humor perch for Christopher Buckley, and the place where Steve Martin made his literary debut.

Mission Accomplished

Fast-forward six years-- to ten National Magazine Awards, including The New Yorker’s first for general excellence, four George Polk Awards, and a 22% increase in circulation. We gave over an entire issue to Mark Danner’s searing exposé of the hidden massacre of a thousand villagers, more than half of them children, in El Mozote, El Salvador, by U.S.-trained Salvadoran Army troops. We published Philip Gourevitch’s remarkable and disturbing story about the 1994 Rwandan genocide. I hounded Mark Singer, one of the old guard’s greatest descriptive writers, to do a stinging profile of Donald Trump, who called me to deliver a tirade, shouting, “You told me I would love the piece and you lied!” (Yup, Donald, the goal was to get you to say yes.) The piece contained the classic Trumpism: “This is off the record but you can use it.” He later penned a Sharpie note to Singer that read, “Mark, you are a total loser! And your book and writing sucks!” Framed, it now hangs in Singer’s bedroom.

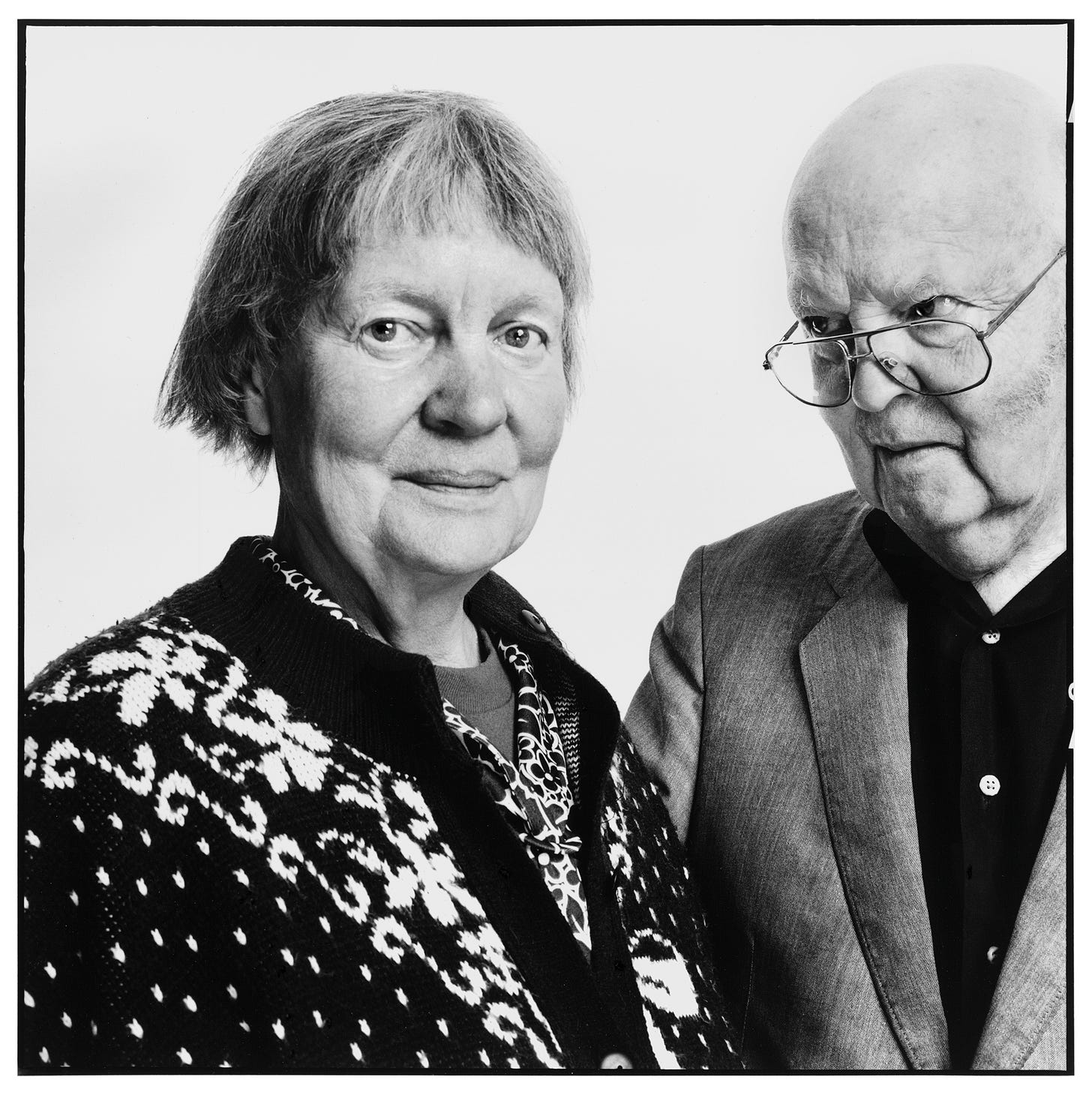

On the afternoon of July 8, 1998, a sense of happy industry permeated the editorial floor. As I passed the offices of such beloved colleagues as the fastidious wordsmith Virginia Cannon, the swashbuckling fiction editor Bill Buford, and the master prose polisher Jeffrey Frank, I paused to savor it all. The magazine was on deadline with one of its finest issues. The lead (called “the well”) was a meditation by Oxford academic John Bayley from his book about the decline from advanced Alzheimer’s, of his wife of 42 years, the novelist Iris Murdoch. “Our mode of communication seems like underwater sonar,” he wrote in Elegy for Iris, “each of us bouncing pulsations off the other and listening for an echo.” To accompany the piece, Avedon had captured the aging Iris and her husband with stark intimacy. Against a white background, Iris stares at us with an expression of childlike joy as Bayley scrutinizes her with interrogatory disquiet. Elsewhere in the issue, in a gritty change of pace, the investigative reporter Jon Lee Anderson dissected the rationale of American liberals who continued to support Liberia’s bloodthirsty president Charles Taylor. As I walked past the row of offices and the purposeful esprit de corps of this extraordinary cadre of writers and editors, it was particularly poignant to me because I knew something they did not: it was my last day. My job was done. After all the work, The New Yorker was …. perfect. Time to go.

In the 27 years since, I have watched David Remnick, my successor, become the inspiration, protector, and cultivator of The New Yorker’s expanding field of talent, a level-headed leader in hot-headed times. He has navigated the magazine through the most precarious of American moments – 9/11, the rise of Obama, the curse of Trump -- without ever succumbing to hysteria or undue glory, preserving the magazine's peculiar alchemy of writing and reporting, and its endurance as an island of sanity and truth. May it still be thriving 100 years from now.

I've often thought it a privilege to come across an exceptional piece, a compelling narrative, a brilliant book. That's how it feels to me reading your evocative piece about your years at The New Yorker. Thank you.

What an achievement! Love the peek behind the masthead--and Newhouse writing to subscribers is unbelievable! Does this mean we'll be able to read The New Yorker Diaries one day??